1.

A group of women talk about raising children.

“They a pain.”

“Yeh, Wish I’d listened to mamma. She told me not to have them too soon.”

“Any time atall is too soon for me.’

“Oh, I don’t know. My Rudy minds his daddy. He just wild with me. Be glad when he growed and gone.’

Hannah smiled and said, “Shut your mouth. You love the ground he pee on.”

“Sure I do. But he still a pain. Can’t help loving your own child. No matter what they do.”

“Well, Hester grown now and I can’t say love is exactly what I feel.”

“Sure you do, you love her like I love Sula. I just don’t like her.’

In the distance, out of sight but close enough to hear, a daughter listens to her mother.

–I had no idea I was wounded. I had no idea that the wound that tore apart my body wasn’t supposed to be there. There was no internet back then. No impulse to self-diagnose, no desire to share stories with others like you.

I never talked about the wound, and coworkers that caught me crying in my car during breaks or strangers that found me huddled in a ball on the floor of the bar bathroom worked to not see it. Friends scratched around for answers, got a fistful of my blistering silence, then dropped it for good.

A mother’s love is precious. Pure. Godlike. The smooth white of clean sheets, the cool tenderness of soft hands on flushed cheeks. Eyes that crinkle with joy, eyes that never lose track of the child, the beloved. My beloved, says the mother, her voice, angel wings whisping through full lips, wrapping the child in protective love.

And then there was the woman in the house that I grew up in. The mother. My mother. Who feasted on my blood, sharp white fangs piercing my tender baby skin, ripping and tearing until embedded in the life giving vein. The mother who promised me the pain from her fangs, the light-headness from loss of blood, the ragged edges of the wound that never healed enough before she pierced it again, were good things. Normal.

I had no idea I was wounded. But I knew something was wrong. I knew she was killing me.

But it was her I wanted to save.

I was a good girl. Such a good girl.

2.

She got out of bed and lit the lamp to look in the mirror. There was her face, plain brown eyes, three long braids and the nose her mother hated. She looked for a long time and suddenly a shiver ran through her.

“I’m, me,” she whispered. “Me.”

Nel didn’t know quite what she meant, but on the other hand, she knew exactly what she meant.

“I’m me. I’m not their daughter. I’m not Nel. I’m me. Me.”

Each time she said the word me there was a gathering in her like power, like joy, like fear. Back in bed with her discovery, she stared out the window at the dark leaves of the horse chestnut.

“Me,” she murmured. And then, sinking deeper into the quilts, “I want…I want to be…wonderful. Oh, Jesus, make me wonderful.”

–I escaped. I was alive.

I am me.

Me.

But I didn’t know I was traumatized. I didn’t know that picking at the Mother Wound, tearing off the growing scab, pushing the blood out of my body on my own. Falling into anemic sleep, dreaming of dying, were all signs of trauma. It just felt normal. And I missed being needed. I missed having a job. Being a good girl. If I wasn’t a good girl, what was I?

Who was I?

There was no internet back then. Only your small group of high school friends or your even smaller group of work friends. You didn’t meet people outside of your city, you didn’t google ‘mother, wound, help.’ There weren’t thousands of pages of returns of people struggling through a trauma you recognized.

There were only books. The Bluest Eye. Beloved. Sula. And in those books, there were the people you meet online now.

The daughter wounded.

I just don’t like her.

The mother that killed.

“Is? My baby? Burning?”

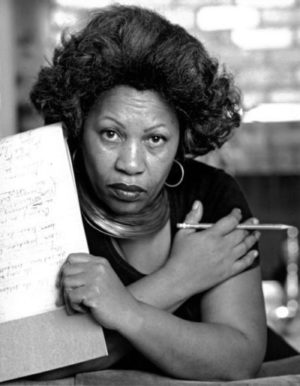

Toni Morrison knew that in this world, there are mothers that hate their children, even if they love them. She knew that there are mothers with love so big, it eats their children alive. But she also knew the voracious will to live in the daughter, feral, hungry. Wounded maybe, but there. Wounded maybe, but like water, always finding a way around the mother, a way to rebirth itself. A baby climbing stairs. A daughter with her own opinion. I am me.

Who was I? I didn’t know. But I am me. I escaped, I saved myself.

I am alive.

Toni Morrison saw that. And honored it.

Oh Jesus, make me wonderful!

3.

Because all that freedom and triumph was forbidden to them, they had set about creating something else to be.

–I escaped. I was alive.

Now what?

Toni Morrison knew.

You lance the wound. You clean it. You rest. You eat. You dance in the woods. You laugh. You cry.

“Lay em down, Sethe. Sword and shield. Down. Down. Both of em down. Down by the riverside. Sword and shield. Don’t study war no more. Lay all that mess down. Sword and shield.”

And then you get back up, again. This is life.

Toni Morrison also knew:

Freeing yourself was one thing; claiming ownership of that freed self was another.

Life doesn’t just stop because you are free. When you are free, you have a whole new world of things to worry about, to consider, to create. Getting up is important. You can’t claim yourself if you are not up off the floor. But it’s the claiming yourself part that has to be done, no matter how hard. For your past, for your future. For your now.

You will hear Toni Morrison called all sorts of things in the coming weeks. A National Treasure. An American Hero. A Literary Genius. All of these labels are true. But she was also just a woman, as well. A black woman, born and raised in the midwest. Ohio.

And Toni Morrison refused to allow the escape to be the end of it. She struggled through the problems of the living. How do you live? How do you create something else to be, when the fullness of ivory fangs embedded deep in your alive tissue is what feels normal and right? When you think those ivory fangs are what you want? How do you live–actively?

Lay all that mess down. So you can set about creating something else to be.

Toni Morrison saw her son get sick, then die. She had deep painful regrets. She knew the wound’s aliveness will leave on a body. And she made the choice towards compassion. Love.

Mothers that are allowed to heal.

You your best thing, Sethe, you are.

Daughters becoming their own best thing.

I have my own opinion.

She gave the gift of a continuing story to black women. And in that way, the rest of us were blessed too.

What is my story? That I can ask this, allows me to be an active author in the writing of it. I can decide. I can make a mistake, back up, try another route. I thought I missed those fangs. I thought I loved them. That they defined me. Life let me see the truth. So I backed up, and tried again.

When I wrote my own story, when I let the Mother Wound scab over and fall off on its own, I stopped missing the feel of the fangs. The pleasure receptors in my tissue grew back, full and lush and deep dark velvety red. Joy and new possibilities grow from within me, even as every once in a while, as life will have it, I get knocked down. Toni Morrison gave me an active voice.

Toni Morrison saw suffering, and offered peace, compassion. She saw indescribable pain and gave language. She saw the clawing white fangs and said no. She saw the stories that were never written, listened, then wrote. She was a black woman that made that choice. She gave us our hearts and told us how to hold on to them. Because she knew that was the prize.

Toni Morrison was a woman the world required. I will miss her every day.

4.

And the loss pressed down on her chest and came up into her throat…it was a fine cry–loud and long–but it had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow.

This is really beautiful. You should write more.